Manning Clark's second coming

Peter Ryan recalls Australia's eccentric Leftist historian Manning Clark, whose anti-heritage influence persists with a reissue of his "History" expected

Charles Manning Hope Clark took up a newly created lectureship in Australian history at Melbourne University in 1946. He and controversy arrived on campus arm in arm, a bond not broken even by his death in 1991; since then, from underground, his remarkable personality has sporadically re-entered the news, as frequently in relation to his politics as to his scholarship.

For example, two recent books mention Clark. The first, Andrew Roberts's A History of the English-Speaking Peoples Since 1900, is a 750-page blockbuster. Intending readers from the chattering classes are warned Roberts may well drive them close to apoplexy even before they get up to the Boer War. He devotes about three pages to Manning Clark.

The second book is a paperback called The Life of the Past: The Discipline of History at the University of Melbourne. Edited by Fay Anderson and Stuart Macintyre, it is the story of Melbourne's history department, told by itself. Much of the content is of such inconsequentiality that it is surprising to find no mention of the Great Tea Trolley Disaster of 1936. The index contains about two dozen references to Clark.

Roberts notes Clark's incapacity to handle mere facts; his failure to provide insightful accounts even of such fundamentals as Federation; his wordy imprecision; his boring and near-psychopathological hatred of England and the English; his enduring Stalinism ("the Communist Party was for many the conscience of Australia"). All this, says Roberts, and more, has over 20 years been "pumped into the Australian academic system", where much of it still lodges. Roberts, clearly, feels that now may be the time to see Clark and all his works filed away permanently under "Australian intellectual embarrassments".

How is Clark treated at the hands of Anderson/Macintyre and their 23 contributors? Very gently. His dented reputation (whether as scholar or as public figure) is massaged tenderly around the bruised parts. By fudging (and a smidgin of actual falsehood) Clark appears as a still-respected Australian history ancestor-figure.

An illustration of our historians' method is their account of A History of Australia - the Musical. In 1988, Clark's six volumes were adapted for a stage musical. Bob Hawke and the entire Labor who's who graced the opening night at Melbourne's Princess Theatre. We are told that this was "perhaps the most original spectacle of the Bicentennial year". We are not told that it was a ghastly flop, rushed red-faced off the stage after a run of a few days.

Why do today's historians so staunchly rally to Clark (1915-1991), whose work has shed upon their craft little but suspicion? For Australia, a less worthy symbol of high historical scholarship would be hard to find. As an undergraduate at Melbourne, his professor judged him to be a second-rater; he returned from Oxford without completing his degree. He lectured first in Melbourne's political science department, moving to history to teach the new Australian course in 1946. Macmahon Ball, founding professor of political science, was relieved that "someone so dangerous and unstable" was no longer on his staff.

Clark's early lectures - ask anyone who attended them, as I did - were brilliantly alive; they sparkled with his own fresh enthusiasm for his new subject. The tutorials for his honours students were inspirational. These were his days of bright promise.

The historian Geoffrey Serle, my near contemporary, was another ex-serviceman student of Clark's who fell under his short-lived spell. Serle was one of only three people who knew that, even before Manning's death, I was working on a sharply critical essay. He encouraged me to proceed, but he saw no draft. He discreetly helped me to manage the enraged historians when the storm broke.

Clark had set his heart on Melbourne's new (second) chair of history. When it went instead to John La Nauze, Clark seemed at times almost unhinged by disappointment and envy; he revealed unbecomingly the "spoiled child" who survived in the grown man. In 1950 he moved to Canberra, to remain professor of history at the Australian National University until retirement.

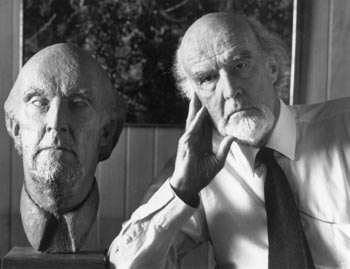

It was here that the showman-like persona was developed: the broad-brimmed hat, the stout boots, the pilgrim's staff, the beard. I tried to tease him as the costume took shape, but he agreed, with perfect good humour, that he was turning himself into a character, rather like Edna Everage. In 1978 Patrick White, launching volume IV of the History, told the audience that Clark's attire was "just one of his gimmicks".

With the creation of the persona went the writing of the History, some 1.3 million words. Re-read today, this great undertaking is a dispiriting let-down. It bristles with Clark's bias and his many prejudices, some apparent and others camouflaged. To any ear attuned to the latter half of the 20th century, his rantings about the Australian "bourgeoisie" sound like leftovers from some Labour Club student meeting of the 1940s. Over it all lies a heavy load of humbug.

"Bourgeois Yarraside" he described as a moral horror, and his own school, Melbourne Grammar, as a particularly odious manifestation of it. But he had four sons, and it was to Melbourne Grammar that every one of them was sent. Clark was bourgeois to his bootstraps, living in a Robin Boyd house in a splendid part of Canberra, owner of several properties, and with a beady eye attentive to his own financial interests. He was deeply and knowledgably immersed in bourgeois culture - its literature, art and music. But all such sympathies were banished from the History, where every "bourgeois" must be a crass materialist, a "Mr Moneybags", grinding the faces of the poor, and watering the workers' beer.

To Clark, the story of Australia's people and their struggles did not exist, with its own independent dimension and validity; it was mere raw material for a drama to be written by him; real historical personages became his characters, to be suitably bent as dramatic circumstances required. Among many others so remodelled were the explorer Ludwig Leichhardt, and prime ministers George Reid and Edmund Barton.

Heavily made over by Clark were R.G. Menzies and H.V. Evatt. The first he portrays as a colonial booby, "grovelling" (a favourite Clark word) to the Brits. Allan Martin's fine two-volume biography of Menzies proves this to be nonsense. Evatt, Clark tells us, believed that "Labor was the Magic Flute leading Australia up into the light"; Evatt had "the image of Christ in his heart".

Chief justice Owen Dixon, with years of experience with Evatt on the High Court bench, and in stressful wartime diplomacy, judged him to be "psychotic, evil and cruel". Nobody used the English language with more fastidious precision than Dixon. I have known many men who dealt at a high level with Evatt, but not one who would have disagreed with Dixon. It shows the folly of Clark's method. His drama, to be sure, required two strongly contrasted characters, but that is no way to write history.

The dangerous instability earlier detected by Macmahon Ball persisted. An Australian delegation flying to a Moscow writers' conference comprised Clark, Judah Waten and the old-time socialist poet James Devaney. Clark and Waten behaved so outrageously that a humiliated Devaney asked the hostess to move him to the back of the aircraft away from them. On their return to Australia, and with great merriment, both Clark and Waten described to me their exploit. They had no sense that they had made conspicuous louts of themselves, while travelling as representative Australians.

There is every likelihood that Clark was a lifelong Stalinist. He was recruited to Melbourne's political science department by Ian Milner, the famous "Rhodes scholar spy". After Milner fled to Prague, Clark went to see him there in 1958 and 1964. Strenuous efforts by the Brisbane Courier-Mail in the '90s to establish the full details of Clark's relations with the Soviets are today brushed aside by Macintyre as "an absurdity"; he does not mention Clark's '60s references to Lenin as "Christ-like ... in his compassion ... lovable as a little child." Lenin?

Macintyre states (page 368) that Peter Ryan's "posthumous campaign" dwells on Clark's early Melbourne years. Untrue. My Quadrant essays (September and October 1993, October 1994) cover the whole of Clark's career and all his published books. I wrote out of puzzlement that a history so flawed and so badly written could continue to work its spell with academics and schoolteachers; their response was quick and violent.

Macintyre was the leading attack dog, and he snarled that I was a coward. The rest of his pack bayed that I was a cannibal, mad, a knocker, a dirty pool player. Paul Bourke from ANU called me a pornographer, and then prime minister Paul Keating added bitchy. I received anonymous hate mail and threatening phone calls, and was assaulted by a Clark fan in a bar in Carlton. But despite all the displays of high animal spirits, they never attempted to answer even one of the specific questions I had asked. They remain unanswered in 2007. All this was water off a duck's back. But it showed that I had offended, not a body of scholars, but the adherents of the cult of Clark, whose memory gave the Left comfort.

The Melbourne historians might have been prudent to use the opportunity of their new book to bid Clark a tactful, and even an affectionate farewell, but it seems that the veneration of the saint is to continue. Do their prophets even foretell a second coming? One substantial biography of Clark is certainly on the way, and I have heard rumours of another. A recent telephone inquiry to the sales department of Melbourne University Press drew the reply that a reprint of all volumes of Clark's History was a major project for 2008.

I thought about the Southcottians, a numerous cult which formed around the deluded Joanna Southcott in early 19th-century England. It was accepted that Southcott was pregnant by the Holy Ghost, and would give birth to Christ at his Second Coming. The enthusiasm was maintained for years. Would it be unkind to our historians to remind them of the concluding lines of a hilarious poem on Southcott written by A.D. Hope?

A sound like rushing mighty wind Proclaimed the Lord had changed his mind.

(Article above originally appeared February 10, 2007

Back to Table of contents for this site

Back to "Wicked Thoughts"